Ring for the Nurse

1: Camp and Humor in Vintage Nurse Romance Novels

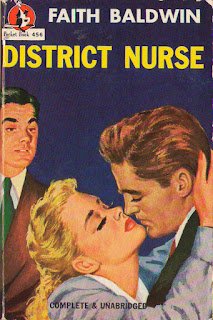

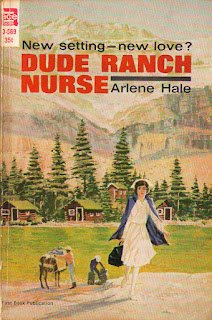

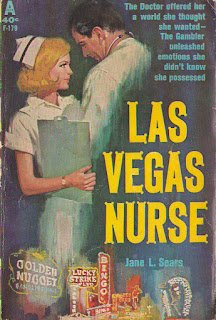

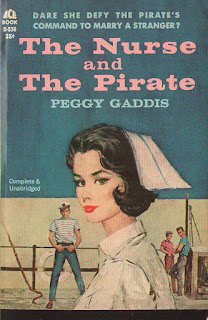

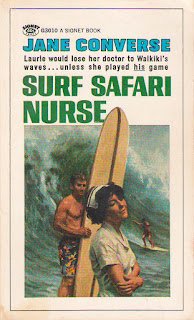

Imagine you’re meandering through a country antique store when, back in the gloomier recesses, you come across a small handful of 50-year-old paperbacks shoved onto the shelf of a rickety bookcase. Exiled from the hidebound classics at the front of the store, a title among this scraggly collection leaps out at you—is that book really called Surf Safari Nurse? You’re instantly captivated. Dude Ranch Nurse, Nurse on Horseback, Cover Girl Nurse, The Nurse and the Pirate—how can you walk away from these neglected treasures?

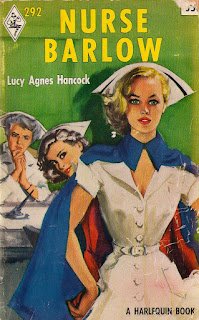

This is actually how I found vintage nurse romance novels, a very niche sector of the romance novel that was widely popular in the 1960s. Indeed, most romance publishing houses, even Harlequin, had a special catalog of nursing titles. Possibly a thousand or more of these books were published up through the 1970s, when they fell out of favor. I was so captivated by their antiquated charm that I now own more than 700 nurse novels, perhaps the largest collection in the world. I’ve even reviewed more than 500 for my blog, Vintage Nurse Romance Novels.

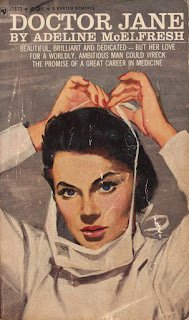

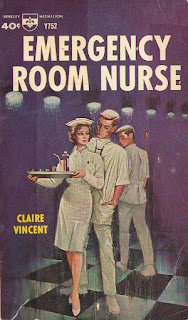

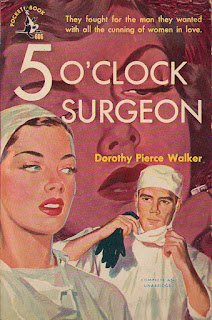

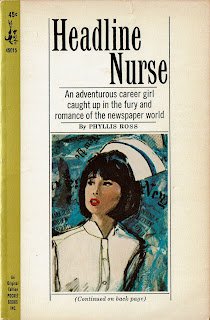

The titles are just the start of the fun: Irresistible cover lines include, “She discovered that medicine and men could be an explosive combination,” (Jane Arden, Staff Nurse) “Heart adrift on a sea of romance,” (Nurse Marcie’s Island) and—my personal favorite—“She was not trained to care for a violent case of love” (An American Nurse in Paris). Cover illustrations by masters of the day offer cherry-lipped women wearing tight uniforms, stiff white caps, and tangible gravitas in the foreground while some out-of-focus man with square shoulders turns to look back at her.

Nurse novels became a thing at a time when women were constrained to just a small handful of careers—teacher, secretary, retail clerk, what was then called stewardess. One of the better options, nursing was a career that demanded competence, intelligence, hard work, and dedication. What it also did was enable independence, right on the heels of the birth control pill, which went on the market in 1960 (and which, interestingly, has not been mentioned once in any of the 225 nurse novels written after that year that I’ve read). With a respectable career and the financial security that came with it, along with new-found ownership of their bodies, women were exploring their options in life and pushing the boundary of stereotypical gender roles. And if readers didn’t have the intestinal fortitude or scholastic chops to make it through three years of nursing school, they could at least vicariously enjoy the struggles of young women making their way in this brave new world.

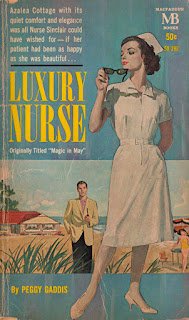

Inside their often magnificent covers, these novels are nothing at all like contemporary bodice rippers—for starters, they are amusingly chaste, seldom showing us more than a kiss. But what a kiss! Instead, these simple stories are about young women and their adventures: their escapades with friends, struggles with patients, turmoil with (usually several) boyfriends. The best nurse novels cavort with camp and hilarity—and, it must be confessed, political incorrectness. “If I’m running a fever, baby, you’ve got only yourself to blame,” says the patient in Celebrity Suite Nurse. “You look like a million dollars in government bonds, that is to say, expensive, hard to acquire, extremely valuable but not exhibiting much interest,” says one gentleman to the nurse in Private Duty. And I’m not sure the humor is always intentional; in Luxury Nurse, the RN in question admonishes, “The marvels of artificial limbs, Lisa, can never be overestimated.” Either way, it’s glorious stuff.

The nurse-heroines are usually smart, hard-working, dedicated women. They chafe at the dichotomy of a rigid and patriarchal world that wants them to be submissive, self-effacing women outside the hospital but independent and strong nurses inside it. When these worlds collide, there’s hell to pay: In A Challenge for Nurse Melanie, the titular nurse saves the life of a man who had choked on his own vomit and passed out in the Blue Ribbon bar by giving him an emergency tracheotomy with a jackknife and a key. When it’s all over, though, the bar patrons are looking at her with “something close to distaste if not dislike.” She gets a warning from the director of nursing for acting outside the scope of her medical practice, and apparently also her feminine practice as well; her fiancé explains, “Everyone thinks it just wasn’t—very ladylike, and that maybe you were just trying to be a—a sort of show-off.” Clearly it would have been better to have just let the man die.

Our nurses usually have a sassy roommate, who goes around saying things like, “A girl who keeps her nerve can have a lot of fun around here,” (Nurse in Paris) and, “Run along to the boy friend and if he starts beating you up or anything, scream. I still pack a wallop” (Private Duty). The roommate is the antithesis of the good nurse heroine: Joan Webster, for example, in The Nurse and the Orderly is a nursing student who is “not the stuff of which dedicated nurses are made.” She sneaks cigarettes in the patients’ bathrooms, and she is constantly agonizing over her endocrinology class—she can’t even pronounce pituitary. But she’s feisty: “They had a long discussion as to whether or not Joan should fix Ted’s favorite spaghetti sauce. If she did, she was a fool. What she should feed the bum if he showed up was a dish of steamed worms.”

These books also give us a glimpse back at the practice of medicine as it was 50 years ago—one that makes me relieved to live in the modern era. Back then, people stayed in the hospital for two weeks for gallbladder surgery (Nurse Marcie’s Island), which now doesn’t even require an overnight. Diabetics were, by the time of their diagnosis, admitted to the hospital in a coma and died, we are told by Dr. Mason, who believes that “most bodily ailments come from some malfunction of a gland” (The Nurse with the Red-Gold Hair). But it’s not all bad: I’ll never forget the symptoms and etiology of pellagra, or niacin deficiency (bodily fluids are involved in copious amounts), after reading Beauty Contest Nurse, which will certainly come in handy next time I have to sit for my boards.

Oh, and there is one certainty with this genre: The nurse always ends up with Mr.—or Dr.—Right by her side and a ring on her finger.

2: Plots of Love

It must be confessed that story lines in nurse novels are not always unique, or even very interesting. Perhaps that’s not too surprising; if an author is turning out a book every month or two, originality takes up too much time. So a number of themes turn up reliably in nurse novels:

The Marriage Plot: Beyond the unexplainable question of why she must marry one of these two (or more) problematic young men in her life, the nurse often starts the book with a steady boyfriend or fiancé. But this fellow is inevitably flawed. Frequently he is working hard to curry favor with a successful doctor in a cushy practice, hoping for a job offer that will enable him to work little and spend lots. Increasingly uncomfortable with this selfish lack of devotion in her young man, she is spending more time with the shy, aloof young medico who seems to have a touch of Asperger’s—and soon she finds the heart of gold underneath. An alternative to this storyline is one in which her unswerving devotion to a longtime sweetie with the appeal of Jello salad is challenged by an apparently uninterested or unavailable man who gives her tachycardia. After chapters of soul-searching, she inevitably chooses love over security, personal integrity over societal pressure.

To Work or Not to Work: Her fiancé is insisting that she stop working when they are married. Interestingly, in almost every case the young man pushing the point has few redeeming qualities, which makes their inevitable breakup a lot easier. But in the interim, many chapters unfold with plenty of internal dialogue over her options: “Could she give up nursing and still be happy? She loved Tom Morrisey with every fiber of her being. But was love, alone, enough? Could she, if she married Tom and did as he demanded, be utterly miserable and still make him happy, make him a good wife?” (A Nurse for Rebel’s Run; the fact that he is planning on working while married is never discussed.) She always chooses the career, but often it seems as though her decision comes about only through the entrance, often through the OR or ER doors, of another man who supports and values her work as a nurse.

The Patient in Need: Whether the patient is a child or a candidate for marriage, our nurse is compelled by her personal dedication to fight for them, frequently putting her job in jeopardy. Take Karen Carlysle, the heroine of Cruise Ship Nurse, who at the book’s open works for society hack Dr. Radcliffe, who is “oozing his bedside best” with a rich, demanding woman with a thyroid tumor. The patient wants an immediate diagnosis, so Dr. Radcliffe pulls out a Vim-Silverman needle for an on-the-spot biopsy. Karen, who had been studying up on thyroid cancer—and why not?—looks upon the doctor with horror and reminds him that a needle biopsy of a cancerous lesion can seed tumor cells, causing metastasis. He drags her into the corridor and, as she argues with him that the procedure is incorrect and dangerous, declares that he will have her license revoked for interfering with a doctor. This is how she ends up on the eponymous cruise ship, where, unsurprisingly, she ends up in another similar situation. But that patient, too, is saved, and Karen is cleared of all wrongdoing in the thyroid case, after sworn affidavits from the patient herself, the cruise ship owner, and the supply room manager. Phew!

The Accused: An accidental death, or at least a major medical malpractice, is perpetrated on our heroine’s shift, and she takes the fall. In Masquerade Nurse, Nurse Kathy’s troubles begin when—her better judgment obviously still on break—she accepts a date with the unctuous hospital administrator, Ralph Knoll. After a steak dinner that includes too many drinks, Ralph predictably puts the moves on, and Kathy is forced to tell the little troll what she thinks of him. So when a terminally ill cancer patient is discovered to have been relieved of his suffering with an unhealthy dose of Nembutal, Ralph is quick to lead the inquisition, declaring that Kathy is guilty of a mercy killing. Though no one believes it, she is nonetheless suspended until the truth can be learned—and the bereaved widow, who just happens to have been given a script for Nembutal recently, is catatonic with shock and can’t answer any questions. So it’s going to be a long suspension, but Kathy’s starched white cap is restored in the end—in no small part because of her heroic role during a horrible accident in the high school gymnasium.

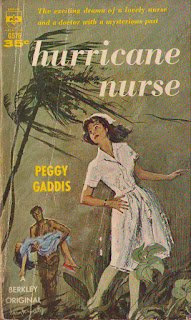

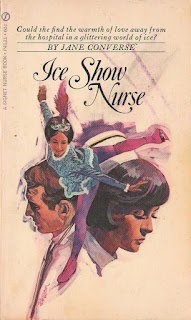

Another World: It could be a Hollywood movie set, a surfing safari, the folk music circuit, a travelling ice show, or an island called Nightmare, Paradise, or Polka Dot. The nurse is: a) running away from some pain (the death of a fiancé or a devastating breakup), b) accompanying (never chasing) the man she loves into a strange world or c) going on vacation when she is pressed to take a job that keeps her in town. Once there, she finds love: When Nurse Katy, the Nurse in Yucatan, finds that a man she met while touring Chichén Itzá has been shot by the father of a child she’s been hired to care for, she treats the man’s wound, of course, even if she’s not confident in her skills: “Everything she remembered from her Medical and Surgical Nursing textbook shouted danger!” She gets him to the village clinic, but the doctor is out. Hank’s rising temperature obliges her to attempt to remove the bullet from his shoulder: “I’m sorry, Hank,” she tells him, “but this is going to hurt like the dickens.” (She has penicillin and sulfadiazine on hand, but apparently they’ve run out of painkillers.) Hank survives the bullet and her ministrations, and when he proposes, “Katy’s world was suddenly as bright as a Yucatán dawn.” If you can stand it.

While certain tropes abound, every now and then something truly bizarre lands in your lap. What is that monster roaming the swamps (County Nurse)? Why is the nurse’s aide so knowledgeable about neurology (Emergency Ward Nurse)? Why is the ghost of a 12-year-old girl’s dead father exhorting the child to kill herself (Challenge for Nurse Laurel)? Is that gang of hoodlums going to take over the hospital and murder the surgery team (Marie Warren, Night Nurse)? What is the deal with that band of wanna-be Nazis who practice marching in the mansion’s basement? (Nurse of Brooding Mansion)? Nurses are abducted by gangsters on at least three occasions (Doctor Dee, Date with Danger?, Emergency Room Nurse, Society Nurse), and five characters have been attacked by sharks—two of them eaten outright, I kid you not (Nurse Farley’s Decision, A Nurse Named Courage, Daredevil Nurse, Surfing Nurse, Surf Safari Nurse). These laugh-out-loud plot twists are just too fantastic for you resist turning to the total stranger sitting next to you on the subway and start reading aloud.

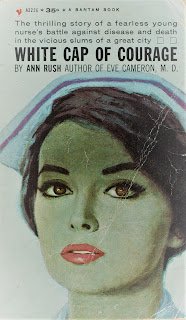

3: Sex in the Nurse Novel

One of the aspects of being a nurse that pops up in nurse novels now and then is that it necessarily puts her in close contact with men in varying states of undress, making it a not unscandalous line of work in the day. When the subject does come up, it is usually only discreetly; “Nursing’s no job for a gently raised girl,” is the general sentiment (White Cap of Courage). On occasion, however, the issue is, well, laid bare: Nurse Melanie’s mother, receiving the news that her daughter was going into this profession, had been shocked: “‘Nursing!’ she had huffed. ‘Seeing men with their clothes off. Seems to me there’s something downright indecent about it!’” (A Challenge for Nurse Melanie)

Then there are the bodily functions, referred to obliquely in the shape of a bedpan or with a comic manner. When nurse Amy Loring, passing by a herd of reporters hoping for news about Senator Matters, who is a patient, happily provides an update: “My patient did have a B.M. yesterday,” she giggles. What a joker!

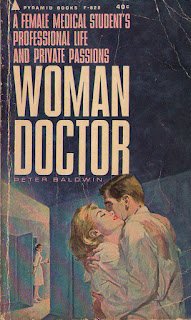

In one most extraordinary passage, the ability to practice medicine is described in sexual terms: In Woman Doctor, medical student Louise Standish “still could not administer hypodermic infections of any sort with the casual indifference of her male colleagues. Her hands were as expert as theirs, but her native femininity was offended on each occasion. Then she came to realize that her instinctive reaction of fear and revulsion was probably deeply Freudian in its origin. As a woman she must find it unnatural and somehow horrible to be thrusting anything into another person. Hers should be the passively accepting role. Not the aggressively penetrating role.” This book was written by a man, Peter Baldwin, and includes a heroine with not one but two actual lovers, and a lesbian couple to boot, so it falls quite outside the nurse novel norm.

In fact, very few nurse heroines have sex. Interestingly, of the three I have found who do, two—the aforementioned Louise Standish, and Jennifer James, R.N. (of the book of the same name)—were written by men. The third, Nurse Jane Walters of City Doctor, was created by Florence Stonebraker, who was a prolific soft porn novel author as well. The overwhelming majority of the time, the only sexual encounter experienced by a nurse is a kiss. But this is no ordinary kiss; you can generally tell by the nature of it how the relationship is going. If she “accepted his kiss without emotion,” (Nurse Gina) it is over! Well, maybe not yet, but it will be. Most of the time.

Far too frequently for comfort, the heroine is grabbed and kissed without her consent. Often the women seem to just accept this as a thing that happens in life, like a flat tire, and their feelings about it are not discussed. In Dr. Jane, Interne, Jane’s long-time doctor friend, Peter Farley, is always calling her “honey” and kissing her in public, though she feels nothing more than friendship for him—apparently just telling him to stop! never crosses her mind. The doctor who works with Nurse Lorena, at one point feels obliged to tell her, “I’m not going to make a practice of this, but I’m going to kiss you, and nothing you can stay will stop me. Relax” (Village Nurse). As astonishing as this statement is the fact that she accepts it, and likes it, to boot.

Oftentimes the kiss is overtly violent: “The hint of savagery that been in his first, interrupted kiss was a surging passion now; it was a long, hard, hurting kiss that became angry as he sensed her lack of response” (A Nurse for Rebels Run). Men not infrequently use a kiss as a weapon of sorts, a moderately chaste rape, to punish women who don’t love them.

There is even overt assault, which is usually described as such. On a date with Chad, Nurse Toni suggests he pull the car over so they can admire the ocean. Big mistake: “With a swiftness that stunned Toni, Chad had her in his arms. His lips were on hers, bruising and demanding. Toni had to fight to break his hold. She was breathing hard as she pushed away from him to the far side of the seat. Chad started to reach for her again, but involuntarily, Toni began to cry. ‘Cut it out. You’re not hurt,’ Chad said roughly” (Nurse Craig). Curiously, the next day she blames herself, though it’s hard to determine what she did wrong.

Another date ends badly in Private Duty Nurse, when Dr. Grant takes Nurse Eleanor to Lookout Walk, grabs her, and, though she struggles to get away, tries to kiss her. She pushes him over a stone wall, but he grabs her again. “I’ll kiss you right, if it’s the last thing I do,” he tells her, and he’s about to when she hits him over the head with a rock to escape, jumps in his car, and drives herself home. It’s almost more outrageous that, for the rest of the book, he talks as if he were the one who was attacked. “I wonder how the Registry feels about private duty nurses who assault people and steal their cars,” he says to her when he sees her next—and she then blushes and asks, “Do you intend to report me?” as if his version is in fact the accurate one.

Psychiatric Nurse (which perhaps not surprisingly won an award for Worst Book on my blog) finds heroine Holly taking a shortcut through the basement of the hospital when she hears a man walking behind her. Frightened, she breaks into an all-out run, and the man runs after her, grabs her with “hard hands,” spins her around “so quickly her feet left the floor,” and shakes her. As she struggles to free herself he squeezes her more and more tightly until “she knew the pain she was feeling was real and not the result of fear.” She’s just about to start screaming bloody murder when he kisses her “hard—on the mouth, shutting off her screams.” Does she knee the rapist in the testicles? Vomit with revulsion? No: “oddly, since she was still in the grip of fear, this sent thrills down to the toes of her sensible nurse’s oxfords. She felt herself go limp in his arms, felt her lips go limp even, and she had to fight an impulse to kiss him back.” Because nothing turns a girl on like sexual assault. The worst part about many of these sorts of attacks, including the three egregious examples above, is that the nurse ends up dating, or even marrying, the man who attacked her.

Spanking is an intersection between sex and violence that comes up with regularity in nurse novels. “I really ought to spank you for being a stubborn little idiot, but I think I’ll kiss you instead,” says one of the many beaux in Nurse of Queen’s Grant, summing up the connection quite nicely. The kink factor is sometimes brazenly acknowledged by a novel’s vixen—never the nurse, of course!—such as when the chief of surgery’s daughter asks the New Doctor at Tower General, “Would you rather kiss me—or spank me?” or when an audacious flirt drawls, “I’m a nasty little cat. Why don’t you spank the livin’ daylights out of me?” (Nurse in the Tropics). When a nurse receives a suggestion that she should be spanked for her audacity, she catches her breath with wide eyes, shocked by what she perceives as a real possibility. From the apparent acceptability of violence against women, to treating women like children, to the hint of sexiness in the act, this could be an entire term paper in someone’s women’s studies class.

4: Authors

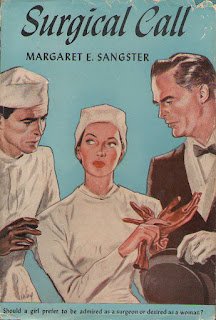

As the nurse novel became a thing, the quality, you may not be shocked to hear, declined. Of the 325 reviews I’ve published on my blog, those published before 1950 earned an average grade of B+. The average grade drops at least one mark per decade: Books published in the 1950s earned a B, the 1960s came in at a little lower than a B-, and you shouldn’t even bother with the 1970s, which whiffed with a C. Some authors, who may or may not have written books in other genres, offered us just one or two nurse novels, while others turned out dozens—and there seems to be no correlation between output and quality. Some of the best nurse novels were written by authors who wrote just one (Nurse Pro Tem by Glenna Finley; Surgical Call by Margaret Sangster), while some extremely prolific writers (Jeanne Bowman, Arlene Hale, Richard Wilkes-Hunter, Dan Ross, Suzanne Roberts) just stunk.

Early nurse novels in particular were penned by some truly interesting writers. What is, as far as I can discover, the first nurse novel, published in 1914, is also the only nurse novel written by Mary Roberts Rinehart. If the title—which, I am sorry to tell you, is “K”—is a complete failure, the prose within is top-notch. But Rinehart, who trained as a nurse and married a doctor, was a ground-breaking writer: She created a character (The Bat) who was one of Bob Kane’s inspirations for Batman, invented the “had-I-but-known” school of mystery writing, was the source of the phrase “the butler did it,” and helped her children establish the publishing company Farrar & Rinehart.

Florence Stonebraker is, in my opinion, the queen of the nurse novel. She wrote at least 22, which may not make her the most prolific of nurse novelists, but she was a delightfully campy writer who could churn out gorgeous, heartfelt writing alongside fabulous lines like, “Every attractive woman should take time out for love now and again. It keeps you young, helps the circulation, and it’s very broadening. Don’t you want to be broadened?” (City Doctor). She wrote hundreds of other novels, a lot of them of the racier variety with titles like Shameless Playgirl and Shanty Town Tease under the pen names of Thomas Stone and Florenz Branch. Born in Washington, D.C. in 1896, she moved to San Francisco in the late 1920s and met a man who left his second wife for her. She moved to Southern California with him and churned out hundreds of novels until she died at age 83 in 1977. You can usually count on Florence for a lively romp, with all the necessary ingredients: a femme fatale wrapped in sable, a sassy sidekick, and even a tiny revolver pulled from a sequined clutch. Just add vodka and a twist of lemon, and enjoy responsibly!

Peggy Gaddis was also quite prolific; she wrote hundreds of novels under her own name and the pen name Peggy Dern. She was born in Georgia in 1895, and most of her books are set in that state. Her heroines tend to be an odd paradox of extremely outspoken, capable women who crumple under the gaze of a man: When Bland Deering (yes, that really is his name) decides to propose, he grabs her by the arm and tells her, “You’re going to marry me, and that’s that!” That’s all it takes: “Her face was wreathed with a radiant smile that lit twin candles in her eyes, and she cried out softly, “Oh, Derry… I’m so tired of deciding things for myself.” This devolves into a nauseating antifeminist conversation in which she agrees to let him “boss me around” because “you’re so much smarter than I am!” He replies, “Now that … is what I call a perfect basis for a perfect marriage—a docile wife and an adoring husband.” If you can endure this sort of treacle, you will get to enjoy her campy side, to wit: “I imagine you are a sensation with Dr. Sturdivant’s feminine patients—you probably have to beat them off with a stethoscope or something” (Big City Nurse), though her tendency toward earnest preachiness also makes her tops in delivering lines that are unintentionally funny, as in: “You mean you don’t know how to do brain surgery? What kind of a doctor are you, then?” (The Nurse and the Pirate)

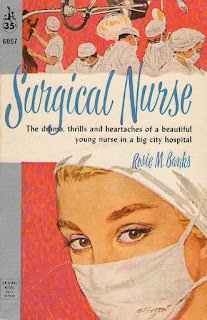

The best pen name in the business is, hands down, Rosie M. Banks, which is itself the pen name of a character encountered in the Jeeves stories by P.G. Wodehouse. The first Rosie was also a romance novelist of the most torrid kind, having penned the renowned Only a Factory Girl and Madcap Myrtle, so this choice by Alan Jackson for his own romantic tomfoolery was completely sublime. Jackson (1906–1965) was a former Saturday Evening Post editor and a story editor for Paramount Pictures, and also penned Perdita, Get Lost and, mysteriously, a breakfast cookbook under his own name. But his four campy novels earned him just shy of a B+ average on my blog, and gave us delightful lines like, “If you look like that, why do you need to say anything?” (Navy Nurse) and, “That girl is no place for a young man” (Settlement Nurse).

Sometimes the writing is just plain beautiful. One particular style of nurse novel, employed by writers including Faith Baldwin, Jeanne Judson, Marguerite Mooers Marshall, Lucy Agnes Hancock, and Adelaide Humphries—who perhaps not coincidentally published most of their work before 1960—paints a leisurely picture of an independent young woman with a satisfying, full life. These women take classes at Columbia, go tobogganing and ice skating, raise someone else’s baby, fix bacon and eggs with their brother—and, of course, go on lots of dates, with at least two or three different men, all of whom they kiss, because “It did not mean anything—a good-night kiss. Not any more. This was the atomic age, not the stone age.” (The Nurse Knows Best)

As the 1960s waned and feminism became more established in America, nurse novels fell out of favor, largely dropped by publishing houses as a stand-alone subgenre by the mid-1970s. As volume dropped, quality plummeted as well: of the 34 books written in the 1970s that I have reviewed, only four got a grade of B- or better. They lost their joie de vivre, too; much like country music, camp as a style left romance novels, which began to take themselves too seriously, ironically only making them more ridiculous in the process. Though today you can still find a contemporary romance novel with a nurse as a central character, her career is a chance detail and not a major draw in its own right.

The confluence of a number of factors emerging in the lives of young American women in the late 1950s—rewarding careers, financial independence, equal rights, reproductive control—brought the nurse novel into being, and the joy and excitement of that time is more than a little evident in the best of these books. Even when combined with truly cringe-worthy aspects of the era, their sense of community, pride, strength, and not least of all humor make them fascinating and fun. So if you are ever perusing a yard sale and come across a book entitled something like Ski Resort Nurse, I hope you will plunk down the quarters and take a chance. Even if it’s a complete disaster, you might still find some promise, or at least a few laughs.